Where’s the literary love for our Kaiju friends?

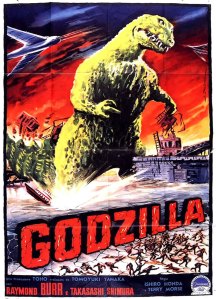

Now, a small caveat is necessary here: serious doesn’t need to mean ponderous, boring, dull, humourless, monotonous, or any of the hundreds of negative words that can be used to dismiss works of art that make us think. By serious, I mean serious in intent and execution; the original Godzilla may have been little more than a man in a suit, yet the film itself conjures up a palpable sense of dread that eluded most of its B-grade creature-feature contemporaries.

To provide just a few examples: Alan Moore’s Watchmen, the Batman Begins series (2005-2012), Perry Moore’s Hero, and Steven Amsterdam’s What the Family Needed all use the superhero genre as a springboard for texts that take a serious look at issues of power, masculinity, control, violence, family, relationships, and free-will. Furthermore, if we look at Jonathon Lethem’s Girl in Landscape, Outland (1981), The Proposition (2005), and William S. Burroughs The Place of Dead Roads, we might see nothing more than a disparate set of texts, yet they are all westerns at their core, and are all of a serious nature. Even post-apocalyptic fiction, which is so often criticised as containing nothing more than survivalist fantasies and uber-masculinist behaviours, can act as the bedrock for po-faced and genuinely moving works of art – Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, The Noah (1975), Steven Amsterdam’s Things We Didn’t See Coming, and Hugh Howey’s Wool series.

Do you notice anything missing from this list? If your answer was ‘giant monsters’ then you’ve obviously been paying attention to the point of this article.

But hang on, I can almost hear you say, wasn’t Godzilla himself just mentioned as an example of how giant monsters can be used seriously? Well, dear reader, you got me there – in the world of cinema, a significant number of filmmakers have approached the genre with thoughts above and beyond merely crafting vacuous exploitation pictures.

In fact, the films that helped defined the genre were themselves often serious at heart. The depth of human feeling invested in the titular King Kong (1933), the unmistakable nuclear parable that is the original Godzilla/Gojira (1954), the melancholy sense of loss that permeates Rodan (1956); these are weighty narrative attributes that both touch us emotionally and engage our intellects. And while it is true that the vast majority of texts that they inspired were indeed vacuous exploitation pictures bereft of heart, substance and any subtext worth mentioning, some recent films have bucked this trend – Cloverfield was unmistakably drenched in allusions to 9/11; Monsters (2010) was explicitly concerned with immigration, dispossession, and asylum-seeking; while The Host (2006) managed to successfully (and humorously) blend issues of pollution, environmental degradation and imperial exploitation with a moving story of a dysfunctional family that pulls together  in the face of adversity.

in the face of adversity.

It is when we look to the written word that we find slim pickings.

This is surprising, as giant monsters seem a perfect fit for our uncertain times – the variety of metaphors that they can embody dovetail neatly with the shifting artistic boundaries and fluid cultural borders that are a part of contemporary life. In other words, giant monsters can mean whatever we want them to mean, as seen in the fact that they can act as stand-ins for nuclear war, 9/11, climate change, pollution and immigration. But whatever it is that we want them to mean, it is highly likely that it is something that has the potential to overwhelm us, to awe us, to dwarf us and make us feel helpless and small. After all, the only feature that giant monsters have in common is their size. In light of this, the vast potential and rich stew of metaphors to be found underlining giant monsters would suggest a well-spring of inspiration for genre-inclined authors.

But no.

In true obsessive-fan style, I spent untold hours researching, borrowing, buying and reading fiction centred around giant monsters. The results were frustrating; the overwhelming majority of what I read delighted in the crash-bang-bash of urban destruction and favoured it over any emotional weight, while commonplace literary attributes such as narrative plausability and convincing characterisation were dumbed down to the nth degree. Thankfully, it wasn’t all bad news – some authors printed in the Daikaiju short-story series took their subject matter seriously, creating convincing worlds and narratives that were truly moving, while longer works such as Mark Jacobson’s Gojiro: A Novel and James K. Morrow’s Shambling Towards Hiroshima engaged in playful and unique postmodern games. However, the limited scope of the short stories left me wanting more, and while the games played by Jacobson and Morrow were undeniably impressive, the playful nature of their narratives somewhat drained away the sense of awe that I enjoy in my giant monsters. To explain: Jacobson’s novel is narrated in the first-person by none other than a Godzilla stand-in, who sets out on a quest to find his world’s version of Dr. Robert Oppenheimer, father of the atomic bomb; Marrow’s novel (set towards the end of the Second World War) tells the story of the American government’s attempt to create a giant monster which can be used as a weapon against Japan, and is told from the perspective of an actor employed to don a rubber-suit and impersonate said monster in a live-theatre piece of propoganda; as could be expected from such brief summaries, much fun is had by all.

I didn’t find a single novel that took giant monsters seriously, nothing that can compare to the likes of Godzilla/Godjiro, Rodan, Cloverfield or Monsters.

Where are they? Are they even out there? Forget creating more works that feature grim superheroes, harrowing end-of-days landscapes, and richly evocative tributes to the western; our writers should be portraying giant monsters as they are meant to be, damn it. Who wouldn’t love a novel that intelligently shows giant monsters as fearsome, terrifying, world-shaking beasts, thoroughly explores the what-ifs of their being, and empathically examines the psychological toll that they might have upon us?

If I don’t find one soon, I might just have to write one myself.

…

Lachlan Walter is a journeyman writer and Phd Student who is fascinated by unloved genres, the end of the world, and all things Australian. He hopes that you’re having a nice day.

Dear Lachlan talk to the boys at Ragnarok Publications about their wonderful Kaiju Rising, Age of Monsters work. Wonderful stuff. Joe Martin and gang are doing some truly cool things. Cheers Leanne Ellis.

I’m actually working on a giant monster novel right now! My influences come more from anime and video games rather than directly from Godzilla. I want to explore the emotional toll the fighting takes on my characters, especially when they don’t even know exactly WHAT they are fighting.